Lesbian Economics

BY: Karen Frost

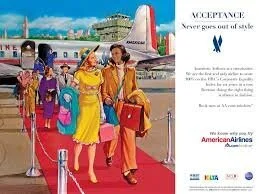

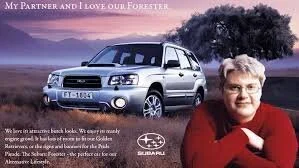

LGBT American Airlines MarketingPhoto by: Subaru LGBT MarketingIndeed, two famous case studies prove there can be big money to be made when companies pitch sales to the LGBT community to capture those pink dollars. American Airlines saw its earnings from LGBT customers rise from $20 million in 1994 to $193.5 million in 1999 after it formed a team devoted to LGBT marketing. (In 2018, LGBT travelers spent over $218 billion a year, one reason the travel industry has laid a particular focus on wooing queer travelers.) Meanwhile, Subaru began marketing to lesbians specifically in the 1990s after it discovered that lesbians were its fifth largest purchaser group, and that lesbian niche market contributed to making Subaru the #2 car seller globally throughout the 2010s. With billions of pink dollars at stake, it’s no wonder that in recent years major corporations from credit cards companies to food companies to alcohol distillers have targeted ads to the LGBT community.

All business is predicated on a simple idea: demand and supply. If there is a demand for a product, the creation of a supply to meet that demand will result in monetary gain for the producer. The magnitude of that gain will depend on the size of the demand and the producer’s ability to effectively fill it. Everyone needs shoes. No one needed the 2001 model Adidas Kobe Two, which look like what Star Wars Storm Troopers would wear when lounging around in their off hours and was such a disaster Kobe ended up buying out his contract with Adidas and moving to Nike.

Producers tailor their production and marketing to key market segments: groups of people who share one or more common characteristic and to whom the product should be at best mandatory, at worst appealing. Consumers should need or want to buy the product, thus generating demand. Normally, the common characteristics of a market segment are things like interests, lifestyles, geographic locations, and demographic profiles. Ideally, these market segments should be measurable, large enough to be profitable, durable, and accessible. In summary, producers want a large and consistent demand that will last for years.

The global lesbian population is approximately 78 million people (1% of the global population of 7.8 billion, a little smaller than the population of Germany), while the total number of queer women statistically should be around 456 million (6%, a number greater than the total populations of the US and the UK combined). As a result of globalism, the individuals in this goliath market segment very likely have a similar psychographic profile and discrete, identifiable needs that producers could fill. Theoretically, they create a demand for particular, marketable products. This means that at least on paper, we’re an ideal customer base. And yet in practice, marketing exclusively to lesbians feels like it has a high rate of failure. Time and again, lesbian-oriented businesses fail. Why? Are lesbians really such terrible customers? Or is there another factor at play?

The “Pink Dollar” is a Huge, Lucrative Marketing Target…

As a market segment, the overall LGBT community punches above its weight. The purchasing power of the American LGBT community was estimated at $965 billion in 2018, making the queer community’s “pink dollar” the strongest of any minority group in the US.

Globally, the LGBT purchasing power was $5 trillion in 2018. This is largely because gay and lesbian couples tend to be DINKS: dual-income, no kid households, meaning they have more disposable income than their heterosexual counterparts. In addition, lesbians experience what’s called the “lesbian premium”: according to a 2015 meta-analysis done by Marieka Klawitter, a professor of public policy and governance at the University of Washington, on average, lesbians earn 9% more than heterosexual women (note that lesbians seem to have a huge pay disparity: they either make tons more than straight women or much less, which is why the average is 9%). Overall, this means gays and lesbians theoretically have more money to spend than straight couples with kids.

Indeed, two famous case studies prove there can be big money to be made when companies pitch sales to the LGBT community to capture those pink dollars. American Airlines saw its earnings from LGBT customers rise from $20 million in 1994 to $193.5 million in 1999 after it formed a team devoted to LGBT marketing. (In 2018, LGBT travelers spent over $218 billion a year, one reason the travel industry has laid a particular focus on wooing queer travelers.) Meanwhile, Subaru began marketing to lesbians specifically in the 1990s after it discovered that lesbians were its fifth largest purchaser group, and that lesbian niche market contributed to making Subaru the #2 car seller globally throughout the 2010s. With billions of pink dollars at stake, it’s no wonder that in recent years major corporations from credit cards companies to food companies to alcohol distillers have targeted ads to the LGBT community.

…So Why do Lesbian-Oriented Businesses Seem to Fail so Often?

Olivia, better known as Olivia Travel, is the world’s largest lesbian-focused company. But 30 years ago, it was a company on the brink of folding. Olivia started in 1973 as Olivia Records, a women’s record label founded by radical lesbian feminists and dedicated to empowering women in the recording business. It made 40 albums and sold over one million records. In 1988, it hosted two sold-out 15th anniversary shows at Carnegie Hall, then the venue’s largest single-grossing event of all time. And yet despite this success, the company was sinking financially. Its founders were idealistic and inexperienced in business, and by the late 1980s, the lesbian separatist movement that had been the engine of Olivia’s success was starting to lose its momentum and be overtaken by a broader feminist movement. By 1990, Olivia was no longer financially viable.

Then it made what turned out to be a massively successful decision. In 1989, a concert attendee suggested a concert on the water. Olivia founder Judy Dlugacz seized on the idea and in 1990 chartered a cruise ship to the Bahamas. 600 women signed up and Olivia’s Travel empire was born. Today, Olivia averages revenues of around $20-$30 million a year. It’s a case study in identifying a market gap and building a product to fill that gap.

Olivia Records’ story mirrors the experiences of many lesbian businesses: despite identifying a market segment, putting out quality product, and trailblazing new successes, they ultimately are unable to proceed financially. Here are just a few examples of high-profile businesses catering to lesbians that have gone out of business in the last decade:

Bars: Even the heterosexual press has noticed the death of the lesbian bar in America. The last lesbian bar in New Orleans, Rubyfruit Jungle, closed in 2012. Philadelphia's Sisters closed in 2013, and San Francisco lost the Lexington in 2015. The oldest continually operating lesbian bar in the United States, Phase 1, closed in 2016. Only a handful of lesbian bars now remain in the US, including Henrietta Hudson, Cubbyhole, and Ginger’s in New York City, A League of Her Own in the basement of Pitchers in Washington, DC, My Sister’s Room in Atlanta, the Lipstick Lounge in East Nashville and the Gossip Grill in San Diego.

The Big 3 NYC Lesbian Bars. Photo Credit: Henrietta Hudson

Photo Credit: Cubby Hole NYC

Photo Credit: Ginger’s Bar, Brooklyn, NYC

Magazines: Like the dodo bird, most American lesbian magazines went extinct before the 2010s. Girlfriends went out of business in 2006, and in an editorial in the 2010 September issue of Curve magazine, then-owner Frances Stevens wrote that without reader assistance in the form of a subscription, gift or donation, the magazine would likely not make it through the year. (Months later, Curve was sold to Silke Bader, who also owns Australia’s LOTL, which was how the magazine survived.)

Websites: Small, independent lesbian blogs run as labors of love by their owners will always exist, but the larger, transnational lesbian websites have really struggled to stay afloat in the mid-2010s. SheWired.com was absorbed by Pride.com in 2016 after it failed as a stand-alone lesbian-centric venture for Here Media, the owner of The Advocate, Out Magazine, and Gay.com. In its perpetually tenuous efforts to stay solvent, Autostraddle implemented a business model with multiple revenue streams including A-Camp, the A+ Membership Program, merchandise sales, advertising, and affiliate commissions. AfterEllen also resorted to reaching out for contributions after it was sold by Evolve Media in March 2019 for failing to bring in sufficient ad revenue.

Bookstores: LGBTQ bookstores peaked in the 1990s, with over 40 operating in the United States. Now fewer than half that number remain, and many have broadened their sales focus to stay in business.

Clothing Lines: Many efforts to create gender neutral or transmasculine clothing lines have failed, although others have continued. At least nine of the clothing companies listed on Autostraddle’s list of 73 lesbian-owned businesses from mid-2018 have closed, including Grayscale Goods, I AM NO LABEL, Kipper Clothiers, Kreuzbach10, Saint Harridan, Ambiance Couture, Apule Town, Equal Period, and FYI by Dani Read.

Anecdotally, many people trying to establish small businesses catering exclusively or mostly to the queer female community have found the market to be less robust than the numbers would seem to suggest at face value. An effort to use indiegogo to fund a new LGBT bar in Philadelphia, for example, ended with only 15% of the funding met. Content creators for webseries and short films have also noted the absence of funding for queer projects. (The webseries “Different for Girls” only generated $1,754 from 16 backers in its Indiegogo campaign for season two, which was 9% funded.)

Success is a Numbers Game, Even for Lesbians

While some lesbian-centric ventures fail, others do spectacularly. Club Skirts Dinah Shore Weekend, popularly known as “The Dinah,” is the largest lesbian event in the world and it’s been happening since 1991. In 2018, over 15,000 women attended. ClexaCon, the world’s largest fan convention for LGBT content creators, allies, and fans, is now entering its fourth year and has been so popular and successful it’s inspired similar conventions in Barcelona (Love Fan Fest) and Tampa (QFX East). When it comes to major annual social events like these, queer women seem to be willing to turn out in droves.

Photo Credit: Dinah Shore

Photo Credit: ClexaCo2018

Photo Credit:. QFX Events

So what’s the secret to the success of lesbian-centric businesses like these? Perhaps the secret is that there is no secret. The queer female business market is, at heart, unpredictable…just as it is for heterosexual businesses. Some androgynous clothing lines fail while others succeed. Some Indiegogo campaigns for lesbian short films blast through their goals while others fall way short. Most queer bookstores are failing because in 2020 people just don’t go to brick and mortar bookstores anymore. And many lesbian business owners, like the founders of Olivia Records, have a good idea but lack the business experience to see that idea translated to financial success. According to the Small Business Association, 30% of businesses fail in their first year, 50% in the first five, and 66% in the first ten. 69-89% of crowdfunding projects (for example on Kickstarter or Indiegogo) don’t meet their funding goals. The truth is, business ain’t easy, no matter the industry or market segment.

Lesbian-Centric Businesses Probably Fail at the Same Rate as Everyone Else

So why does it sometimes seem like queer women aren’t doing enough to help the businesses created for them? Why aren’t they pouring money into failing bars, teetering websites, and cash strapped media projects to support queer causes? The demand seems to exist, so why is there discontinuity between the demand and the supply? A few reasons:

First, there’s a relativity problem here. Most people don’t realize how often businesses fail and therefore they’re surprised when they see such high failure rates. Without data for comparison, however, it’s impossible to say whether lesbian-oriented businesses fail at a higher or lower rate than businesses that don’t primarily cater to the queer female community. Maybe we’re actually doing better than a 30% fail rate in the first year. Until someone does a study, we’re all going off of “gut feelings,” which are notoriously wrong.

Second, as a result of a slew of articles in the last few years proclaiming the death of queer spaces, etc., at least some of us have an anchoring/confirmation bias: once we start to believe that lesbian businesses are being edged out by society, we begin to absorb any new datapoints about failures as proof of this belief while at the same time discarding success stories. If you know one lesbian store/website went out of business, every time you hear about more going out of business it will reinforce that belief. But as noted above, we don’t actually know whether we’re doing better, worse, or the same in terms of success and failure rates.

Third, there is an expectation of altruism/support in our community that isn’t always met. Literature on philanthropy in the LGBT community suggests our community values building and supporting the community. If only 22% of Americans give to Kickstarter crowdfunding campaigns, we might expect our community to give more than that to LGBT projects in an effort to counteract historical marginalization. We might expect our community to prefer queer-run coffee shops or bike stores, for example, and donate to crowdsourcing projects because it gives back to the community. When we see these businesses fail, it may seem to be a reflection of the failure of that community altruism.

Good News, Bad News on Crowd-Sourcing

In the past, I’ve used crowdsourcing for the Brazilian webseries “RED” as an example of how the queer community could do more to support queer projects. Between Indiegogo and Catarse, a mere 156 backers financed season six, 163 backed season five, and 233 backed season four. The point I’ve made in the past is that the first episode of “Red” had approximately 369,000 views. If everyone had paid $1 per view, that $369,000 would have financed around 35 seasons of the show and everyone could have watched for free ever after. It would have been a spectacularly effective and easy funding mechanism.

It turns out, “Red”’s crowdsourcing data teaches us something else about lesbian-centric content, which is this: everything about “Red”’s experience is the norm for crowdsourcing. Nothing changed because it was a lesbian-centric project targeting lesbian consumers. According to 2020 crowdfunding statistics, fully funded crowdfunding projects have an average of 300 backers with an average pledge of $96. The $6,180 raised through Indiegogo for season 4 of “Red” came from 54 backers, which means an average of $114.44 per backer. If “Red” hadn’t had any queer content, it might have received the same amount of financial backing. This trend is borne out by other lesbian crowdsourcing projects, too. Tello films’ “Riley Parra” season 2 Indiegogo campaign raised $21,280 from 192 backers, or an average of $110.83 per backer, while tello’s campaign for “Season of Love” raised $61,157 from 586 backers for an average of $104. In short, lesbian-oriented projects do no worse than anyone else.

Photo Credit: Red the Webseries

Photo Credit: Tello Films Season of Love Film 2019

On the one hand, that’s good news. It shows that fears about lesbian ventures being underfunded may be overblown. But there’s bad news, too, and the bad news is we’re doing no better than anyone else. The queer female community talks a big game about supporting each other and forming an uplifting community, but the data suggests that at the end of the day…we’re as charitable, philanthropic, and consumer minded as our heterosexual peers. No less, but certainly no more. The solidarity within the queer female community does not translate to significantly higher contributions. (By the way, 87% of contributors to crowdfunding campaigns have only given to five campaigns or fewer, showing how hard it is to mobilize crowdsourcing.)

It’s Up to Us as Individuals to Make a Difference

The above indicates that as a market segment, queer women don’t behave in a distinctly different way from any other group. (For the most part. Clearly we love Subarus and Olivia cruises.) Absent further data, there’s no evidence they necessarily fight harder to keep something (“Wynonna Earp” is its own case study) or donate more money or buy more products. That means that while we can’t pull the community as a whole to spend more money at LGBT-run stores or on LGBT-centric projects, as individuals we can make the decision to support these things. Because demand drives supply, if you believe in something, put money toward it. Create demand. If you want to see more ladies kissing on screen, donate to Indiegogo campaigns. Want more androgynous clothing lines? Find the ones that exist and buy form them and promote them on social media. The real lesson here is that we might not be able to move mountains all the time as a community, but as individuals, we can do our best to lift each other up.

Want to make a difference? Here are some exciting web series to support with viewership or fiscally.

BIFL - https://www.bifltheseries.com

AVOCADO TOAST - https://www.avocadotoastseries.com

TWENTY - https://twentythewebseries.com

DELTA AND DAISY - https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/delta-daisy-season-1#/

New York Girls TV - https://www.newyorkgirlstv.com